In 2022, more than 42,000 children were born in Georgia. Yet only about 14,000 women took maternity leave, leaving approximately 28,000 mothers without benefits. Many of those left out were self-employed women.

Lina Gvinianidze, a lawyer and labor law expert, spoke about the situation of these mothers during a presentation of a new report on 19 Dec 2023 titled “Maternity and Parental Leave in Georgia: Legislation, Practice and a Vision for Reform.” The study was published with the support of Open Society Foundation.

The key finding of the study is that maternity leave is not available to a diverse group of women, including women working under service contracts instead of employment contracts, platform workers, couriers, drivers, helpers, nannies and other non-standard workers.

“We have been saying for years that maternity leave should be improved, but who are we talking about? Which women are we talking about? Because it seems that the current decree on maternity leave is a benefit intended for a very small group, and thousands of women are left outside this system,” Gvinianidze said.

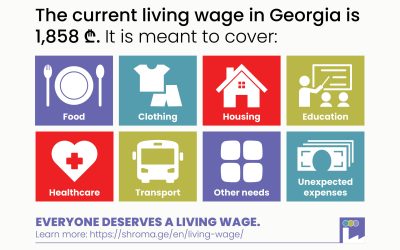

The current system also creates inequalities for women who do qualify for maternity leave – namely between those in the public and private sectors. Paid parental leave in Georgia lasts 6 months by law. But under current legislation, women working in the private sector only receive remuneration in the form of a one-time benefit of 2,000 GEL, meaning they receive 333 GEL per month. By contrast, women in the public sector generally receive their existing monthly salary for the full six months.

The study also found that low prevailing wages prevent women from returning to the labor market after maternity leave. This is problematic because the lump sum maternity leave payment is generally not enough to cover the costs related to having a new child, meaning women and children become even more reliant on help from other members of the household.

It should be noted that the existing system of “maternity leave” does not recognize the role of the father in the process at all, because men in Georgia cannot take advantage of paternity leave when a child is born. They can take “parental leave,” but if they do, the mother can no longer take such leave. This provision in the law forces mothers to take advantage of paid leave instead of both parents, which makes it more difficult to share the burden of childbirth.

Mothers interviewed for the study also raised concerns about a need for more postpartum psycho-social therapy services and better information and care services related to parenthood.

The authors argue that Georgia’s current state policy on pregnancy, childbirth and childcare is emblematic of a larger problem of neglecting the social and economic well-being of women and children. They hope that this study will provide new data to inform decisionmakers and others working on this issue, allowing them to build a better maternity leave system.