This May 1 in Georgia, one portion of the workers is out of work while the other toils in dangerous working conditions. The current social and economic crisis is being felt everywhere, from agricultural regions to big cities, from tourist areas to production centers. For those who have lost their jobs or incomes as a result of the pandemic, it is unknown when new employment opportunities will arise. Those who have not stopped working during the pandemic face gross violations of their rights on a daily basis, with increasing and uncontrolled risks to their safety and health. For workers, the future is vague and contradictory, but one thing is sure: a return to the pre-pandemic state cannot be considered a solution.

At this stage, it is impossible to accurately determine the economic damage caused by the pandemic or to fully record the scale of lost jobs and income. But studies and forecasts confirm that the COVID-19 pandemic is causing a large-scale social and economic crisis. Loss of jobs and income cannot be fully accounted for because the pandemic has significantly affected not only those employed in the formal economy but also the informally employed, including traders, domestic workers and many others. The informal sector is typically highly sensitive to economic fluctuations, as it is dependent on domestic demand, and Georgia’s limited legal protections for workers do not apply to informal workers. Moreover, some informal workers were unable to access anti-crisis assistance in 2020 due to the lack of necessary documentation, vague criteria or lack of access to relevant information.

The COVID-19 pandemic had varying effects on different types of workers. For example, due to unequal redistribution of domestic labor and care and disproportionate gender representation in the informal sectors, the COVID-19 pandemic “worsened the situation of women in Georgia and deepened gender inequality.” [1] Student-workers were affected as well: Even as incomes fell, tuition fees did not change. As a result, the number of suspended students was estimated to exceed 70,000 in 2020. [2]

Last year turned out to be a year of unemployment for the vast majority of those employed in the service and tourism sectors, and for workers in the arts and culture industries. Even conservative estimates suggest that more than 200,000 people lost their jobs.

At the same time, the pandemic had a multifaceted and severe impact on the daily lives and legal status of those employees who continued to work in difficult conditions. Nurses and doctors treated patients infected with the new virus at extremely low pay and at the cost of their own health. Garment factories, which produced a product that was fundamental to fighting the pandemic, became centers of infection themselves. COVID-19 infected 116 workers in one garment factory. In the fall of 2020, cases of increasing infection were also reported among subway employees, including 50 drivers. Unfortunately, deaths were also reported.

Due to the need for social distancing, working conditions have changed significantly for social workers and teachers. Without physical visits, the State Agency for Victims of Trafficking, Victim Assistance, and other social workers are no longer be able to establish direct, physical contact with beneficiaries, making it difficult for them to perform their duties. The transition to online teaching has fundamentally changed the education process not only for students but also for teachers who have had to acquire new skills and develop new lifestyles.

Sectors free of economic constraints, such as the mining industry, have seen even more severe labor rights violations and deteriorating safety in an already dangerous work environment. In the Tkibuli coal mine, where the nature of the job often does not allow for social distancing, COVID-19 has infected more than 140 miners. During the pandemic, key, irreplaceable work was performed by contractors and couriers who sacrificed their own health to make life easier for the rest of us in lockdown.

During the pandemic, cases of unjustified dismissal, unlawful termination, unpaid leave, and forced work have become more frequent. Particular challenges included the adequate remuneration of overtime work, the regulation of online work, and employers’ unilateral changes to the substantive terms of employment contracts.

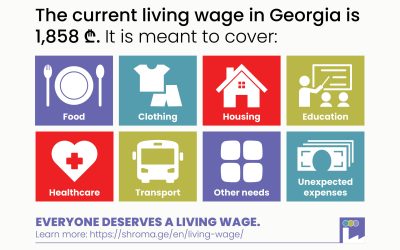

The pandemic’s effects on labor were worsened by the absence of fundamental legislative tools to protect workers. Georgia’s lack of an effective minimum wage, for example, has resulted in a situation where more than 300,000 workers make less than GEL 200 per month. This left many workers extremely unprepared to deal with pandemic job losses and/or income cuts. Due to the lack of unemployment insurance and benefits in Georgia, workers were at risk of destitution upon losing their jobs.

The current economic crisis presents a prime opportunity to rethink Georgia’s labor policies, but the country has thus far failed to do this. Rather than instituting state programs to create jobs and stabilize the labor market, for example, Georgia’s anti-crisis policies have largely focused on privatizing state property and natural resources. The government appears to see labor migration as its preferred way to solve problems in the labor market.

According to GYLA research, the loss of jobs and incomes by the population during the pandemic has also put many at risk of defaulting on their loan obligations. Banking institutions extended loan terms to individuals via a 3-month grace period, did not suspend the accruing of interest during this term. As a result, many borrowers have to pay more each month than they did before the pandemic. Some unemployed borrowers are subject to collection proceedings, putting many families at risk of losing their homes.

The pandemic has revealed that some problems faced by workers in Georgia are also being seen abroad. In Tbilisi, the demands of app-based delivery couriers echo the protest calls of couriers in several countries around the world, and set an important precedent for the self-organization of workers in a rapidly growing sector. At the same time, the actions of traders dealing with new needs arising from pandemic constraints provide a striking example of informal sector self-organization.

From January 1, 2021, several important amendments to the Labor Code came into force. As a result of these reforms, which were adopted by the Parliament of Georgia in the fall of 2020, the mandate of the Labor Inspectorate has been expanded, giving them the power to investigate not only labor safety issues but also general labor rights violations. The initial draft of the reforms was far more ambitious than the enacted bill, but as a result of an opaque drafting process and active lobbying by large businesses, a number of important provisions were ultimately removed. Nevertheless, if properly enforced, the labor reforms could help tangibly improve workers’ daily lives and create opportunities for positive future change.

It should be noted that the Labor Inspectorate was tasked with enforcing a wide range of restrictions and regulations imposed due to the pandemic. This has significantly limited their ability to conduct normal workplace inspections. Consequently, it is still unknown to what extent the Labor Inspectorate, which already suffered from a lack of resources, will be able to work effectively within its expanded mandate. Both the success of labor reform and the institutional sustainability of the Labor Inspectorate will depend to a large extent on the Inspectorate itself being able to effectively carry out its full mandate and significantly improve the working conditions of workers.

May 1 is International Workers’ Solidarity Day. The multifaceted and pervasive crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is proof that the current political and economic system fails to provide a sustainable, fair and secure daily life for workers and their families. The crisis also confirms the need to fight against this system and secure fundamental change.

Fair Labor Platform member organizations:

- Center for Social Justice;

- Trade Union in the field of health and services – “Solidarity Network”;

- Open Society Foundation-Georgia;

- Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA);

- Union of Social Workers;

- Tbilisi Metro Independent Trade Union – “Unity 2013”;

[1] COVID-19 has exacerbated the situation of women in Georgia and deepened gender inequality. Gareo Women’s Organization. 17.06.2020

[2] Correspondence of the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Georgia, November 1, 2020.